Miral’s Mystery: A Film Analysis

Born and raised in Jerusalem in the second half of the

twentieth century could confuse one’s identity. Palestinian versus Israeli.

Muslim Arab versus Muslim Israeli. The longest and most fought-over city in the

world was the location of the film Miral.

Miral was the name for the red flower that grew on the side

of the road in Jerusalem. This flower was a witness to lots of the pain and

change in the lands of Israel and Palestine like Miral, the film’s protagonist.

|

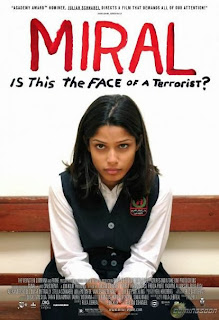

| Image from Google Images |

Miral was born to a mother who underwent sexual abuse as a

child and an imam father who loved her mother despite of her pain and

addictions. Miral came of age in an all-girls school. The school was the

product of one woman’s desire to help orphaned Palestinian children during the

1948 war. Each subsequent war brought more orphans and more girls. After Miral

lost her mother, her father decided to send her to the girls school for her

education and well-being because her father was one of the principal caretakers

of Al-Aqsa Mosque. Miral reached the end of her adolescence in the wake of the

1987 Intifada, the first Palestinian uprising against the Israeli occupation of

Palestinian territories. By the end of the film, Miral had to decide between using

violence or her education to bring piece to her homeland.

Catalysts

The film proceeded in a multi-generational and catalytic

approach. The film spanned from the period right before the 1948 War to the

time following the first Intifada when the first Oslo accords were signed. The

first human catalyst was Hind Husseini (a.k.a. Mama Hind) who took in the

orphaned Palestinian children. She became the headmistress of the girls school

and a major player in Miral’s life when Miral had to decide between terrorism

or education as the answer to a free Palestine.

The second catalyst was Miral’s mother, Nadia. A victim of

sexual violence, Nadia chose to heal her wounds with alcohol, which is

forbidden by Islam. Nadia’s husband, Jamal, tried to love her away from the

alcohol, partying and depression, but her demons were too strong. Nadia’s early

death via suicide in the sea left Miral searching for answers later in life and

trying to define her identity in the Intifada.

Other major catalysts were Miral’s father, Jamal (one of the

imams who oversaw Al-Asqa mosque), and Hani, Miral’s lover. It was Hani who

introduced Miral to violent resistance to the Israeli occupation, but Hani was

also the one that convinced Miral to turn away from violence to join the

Palestinian Liberation Organization’s (PLO) move for a peace agreement with

Israel. Despite Miral’s decisions to enter violent protests or to defend Hani’s

reputation against the Israeli police, Miral’s father, Jamal, remained as her cornerstone

in order to defend his daughter and rescue her from her consequences by sending

her to first live with her aunt and then gaining her release from the Israeli

jail.

The Expressive Use of

Cinematography

The cinematography in the film really played a major part in

highlighting the major catalysts in the film. The bold screen shots of the

characters’ names between scenes emphasized the role of the character in

respect to Miral. There was nothing lovely or cute about the screen shots, but

they were rather raw in how the names quickly appeared on screen in white and

all caps against black backgrounds. This use of cinematography captured the

grit and rawness of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, how the horrible details

of the Israeli occupation could not be covered up by the settlements or the police

brutality against Israeli citizens and Palestinians (e.g. disregard of Miral’s

Israeli citizenship rights when beaten by the police).

How to End Conflicts?

The larger theme of the film was how to solve conflicts.

Could one solve conflicts by violent resistance, or was education and politics

the key? Miral’s school’s headmistress, Mama Hind, always encouraged the school

girls to follow the way of education to solve Israel’s and Palestine’s

problems, not violence, which could result in death. This was the case for

Miral’s friend, Hidal, when they both attended a protest against the Israeli

occupation, which resulted in Hidal’s accidental death.

By the end of the film, there was a brewing peace agreement between

Israel and Palestine. Miral was exhausted by the death of her father and then the

unforseen assassination of her lover, Hani. The audience could have thought

that Miral would return to violence to avenge her lover’s death, but the First

Intifada had left Miral vigilant, having learned that violence was not the way

to approach peace. Mama Hind met Miral in her grief and encouraged her to start

a new life with a scholarship to a European university. Mama Hind convinced

Miral to find a solution to end the conflict in education, not in picking up

guns.

The debate on how to end conflicts (e.g. violence versus

education) has existed for decades and centuries. Recent activists like Malala

Yousafzai (the Pakistani girl shot in the head by the Taliban for promoting international

education for all girls) and Greg Mortenson (an American who built schools in

Pakistan to fight terrorism) have come to the forefront of the stage. Their

lives and work are examples of how peaceful protests and peaceful action like

Mahatma Ghandi have made progress in countries around the world. The

autobiographical memoir of Miral,

originally written by Rula Jebreal, is another example of how through

education, conversations can be started, dialogues are initiated, solutions are

posed and conflicts will eventually come to an end.

Comments