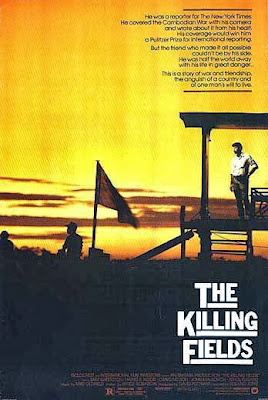

Ignorance Is Survival: A Film Review of The Killing Fields

Cambodia: the name evokes pictures of poverty and sex

trafficking for many people today. But not so long ago, there was one

government’s genocide against its own people. The film, The Killing Fields,

is a small account of that genocide that took place there in the 1970’s during

the culmination of the Vietnam War.

Sydney Schanberg played by actor Sam Waterston was one of

the main protagonists of the story, but really he is the medium for which the film’s

hero, Dith Pran tells his story. Schanberg was The New York Times journalist in Cambodia right before and at the

set of the Khmer Rouge takeover of Cambodia and its capital, Phnom Penh. Pran

was Schanberg’s interpreter and guide through Cambodia so Schanberg could obtain

the necessary photos and information for his New York Times stories. Schanberg was forced to evacuate with the

other foreigners living in Cambodia once the Khmer Rouge had taken over,

leaving Pran to survive on his own in one of the Khmer Rouge’s labor camps. The

rest of the film focused on Pran’s plight in the labor camp and his escape to

safety afterwards. But Pran passed through nearly death itself when he

witnessed so many killed by the Khmer Rouge in the killing fields.

|

| Image from Google Images |

Actor Haing S. Ngor who played Dith Pran, a real survivor,

had to relive his real, daring escape from Cambodia through this film. Ngor was

able to relate to Pran’s character because both Pran and him were persecuted by

the Khmer Rouge, but both found the will to survive and deny their past lives

as professionals. This element added greatly to the profoundness of the film.

Musical Analysis

Composer Mike Oldfield composed the score for The Killing Fields, using a flare for

psychotic music with bells and chinking of hard metals to help tell the story

of madness in one country. In the scene when Schanberg, Pran and their fellow

Western expats were accosted by the Khmer Rouge, the musical composition for

this scene created a sense of panic with loud banging on cymbals, drums and

other metal objects to allude to the sense of panic, fear and uncertainty felt

by the group facing the Khmer Rouge.

Right before the film transitions from Schanberg’s narrative

to Pran’s, there was a scene where Schanberg re-watched footage he had taken

from the aftermath of the bombings of Cambodia by the U.S. In the background of

this scene was Pavarotti’s rendition of “Nessun Dorma” playing, which with so

much beauty stood at opposite ends of the aesthetically pleasing qualities

spectrum compared to the imagery from the Cambodian Civil War. The choice to

play Pavarotti in the background of this scene where Schanberg was sickened by

the video footage of carnage form the Cambodian Civil Wars belittled

Schanberg’s character as a tool of Western culture to quantify and package wars

and human carnage into something sellable and in a way, aesthetically

stimulating to hungry readers. The juxtaposition of Pavarotti’s song with the

imagery created a sense of desire, consumerism and lack of profound concern for

the plight of the Cambodians except for the use of it being able to profit news

machines like The New York Times for

Westerners. “The hype of the Cambodian carnage could mean something greater as

long as it was stimulating ulterior carnal desires towards violence in the West”

was what this juxtaposition meant to the larger film’s story.

The musical score was almost absent in the latter part of

the film when Pran was living in the labor camp and subsequent escape from it. The

music seemed to only build in the scenes when danger was imminent, for example,

in the scene where Pran was caught sucking blood from cattle. In a way, the

music signaled to the audience of a climatic turning point, which could have

meant the end of one of the characters’ fates. On the contrary, the absence or

the subtlety of the musical score in the latter part of the film made Pran’s

spoken narrative even more important. One could argue that Pran’s narrative was

part of the musical composition, setting the atmospheric mood for the rest of

the film.

Cinematography of The Killing Fields

Dith Pran’s journey to freedom led him through the heart of

“The Killing Fields” and the Cambodian jungle. The scenes of massive gravesites

and rotting human flesh and bones were not for the faint hearted. The rawness

of the cinematography, which was filmed in neighboring Thailand in the 1980’s,

evoked a near sense of the savagery against the Cambodian people.

Dith Pran’s story was one of the few survivors of the

estimated two million individuals who died in the killing fields due to

execution, torture, starvation and other natural causes. According to sources,

Pran’s memoir of his survival first coined the term “the killing fields”. With

Pran’s memoir and other survivors’ testimonies, The Killing Fields could recreate a visual of the mass horror in a

set in Thailand.

Memories from the

Past

In Cambodia, there are several monuments, memorials and

museums dedicated to remembering the approximate two million individuals who

perished during the Khmer Rouge’s reign from 1975 to 1979. In the U.S., a

Cambodian survivor of the Khmer Rouge’s killing fields established a museum in Washington

state, which was dedicated to the remembrance of the Cambodian genocide. An online website serves as the world’s

portal into seeing photographs of prisoners tortured and executed in the most

brutal Cambodian prison, Tuol Sleng, during Pol Pot’s reign. There are so many

ways to remember the brutal Cambodian genocide, and the film The Killing Fields touched just a

fragment of the mass persecution by a government against its people. Let this

film serve as the starting point for many more inquiries into the reasons

behind genocide and prevention of it.

Comments